Liz Lange’s Restoration of Grey Gardens

Liz Lange does not believe in ghosts. In fact, she’s dismissive when asked whether Grey Gardens, the 1901 East Hampton, New York, estate she and her husband recently restored, is haunted. “I didn’t expect to see ghosts because I simply don’t believe in them,” the creative director and chief executive officer of women’s luxury fashion and lifestyle brand Figue says of what it felt like to move in.

Which isn’t to say the past is not present at Grey Gardens. Shortly after purchasing the home in late 2017, the fashion entrepreneur embarked on an extensive restoration of the storied estate, working with architecture firms Ferguson & Shamamian and Bories & Shearron to modernize the operation of the house while preserving much of its original design.

This involved digging a full basement to conceal contemporary mechanical and other functional spaces, shoring up the home’s foundation and structure, protecting original elements like the Dutch front door and foyer banisters during construction for restoration and, when needed, reconstruction, and adding back period-appropriate details like diamond-paned windows and doors with restoration glass—all while leaving the house’s footprint and exterior design nearly unchanged. “Liz and her husband knew that the architectural background they wanted to live in was the one that was built in 1901,” says architect Mark Ferguson, whose firm oversaw the restoration.

More From Veranda

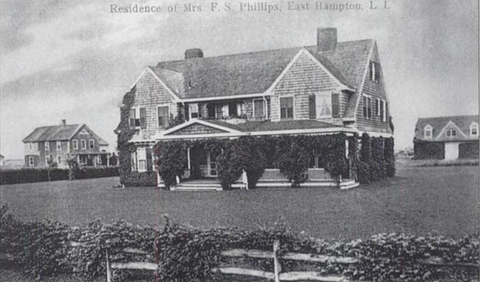

Plans for the original house—an L-shaped, shingle-clad structure with dramatic gabled rooflines and brick chimneys, faint echoes of the English Arts and Crafts vernacular that seeded the American Shingle Style—were designed by architect Joseph Greenleaf Thorpe and commissioned by Fleming Stanhope Phillips. But Phillips died before his vision was realized. Instead his wife, Margaret Bagg Phillips, who famously inherited his estate after fending off challenges to the will from Phillips’s brother, built the house later that year.

To summon the spirit of the original house, Lange changed its flow as little as possible. While some minor floor plan reconfigurations were necessary for the house to live at today’s standards—opening the kitchen to a breakfast room, adding a back stairwell—other alterations, like punching out attic dormer windows on the street side, were avoided to retain the integrity of the original building. Says Lange: “One of the reasons it still feels like an old house is that we forced ourselves not to make it perfect perfect. The floors still creak a little bit, and they are not entirely level.”

The thoughtful revival of its gardens is but another invocation of the property’s past. Lange worked with landscape architect Deborah Nevins on a thorough overhaul of the grounds, planting new gardens in some places and restoring historic elements in others, and facilitating as much outdoor living as possible. Most notably Nevins restored the walled garden, pergola, and thatched garden hut, which had been added by prominent horticulturalist and author Anna Gilman Hill, the second owner of Grey Gardens (from 1913 to 1924) and the first to describe it as such. When reflecting on the garden spaces, Lange describes a distinctive magic. “There’s almost a quietness and you feel like you don’t even know where you are. It has this strangely magical, peaceful, beautiful atmosphere.”

Perhaps ironically Lange’s family history in East Hampton—childhood summers and weekends spent in a rigorously modern house by architect Charles Gwathmey—fueled her passion for Grey Gardens in the first place. “I loved it,” she says of her parents’ home, “but it was not lost on me that the other houses on the street were these older houses…often Shingle Style cottages built at the turn of the 20th century with mature properties and older trees. I grew to think that I wanted a house like that when I had my own.”

It was her love of the house, not its provenance, Lange insists, that prompted her to buy when it came up for sale. She and her husband had rented the house for a summer several years prior and had become smitten with its details, proportions, layout, and gardens. “The landscape struck me as familiar,” she says. “The flow of the rooms just made sense, and it has a really cozy feel, and it’s a very bright house. I worried about it feeling dark, maybe in that haunted way although I don’t believe it’s haunted, but it doesn’t. It’s a very sunshine-y, happy house.”

Lange, who hails from a family who experienced very public financial booms and busts (as she chronicles in The Just Enough Family, her podcast with friend and journalist Ariel Levy) and who became a household name at a relatively early stage in her career with the success of her eponymous maternity brand, is the sixth in a string of prominent, artistic, even visionary women to inhabit the house, each casting a reflection of herself within its design. She bought it from author Sally Quinn, who, along with husband and Washington Post executive editor Ben Bradlee, brought the house back from its near-condemned state, restored many period pieces that came with it, and summered there for more than 30 years, hosting legendary parties with star-studded guest lists until Bradlee passed away in 2014.

The Washington power couple had purchased the estate in 1979 from Edith Bouvier Beale. “Little Edie” lived with her mother, Edith “Big Edie” Ewing Bouvier Beale, at Grey Gardens from the early 1950s until the elder Edie’s death, both in increasing isolation and squalor as they ran out of money to maintain the estate. The juxtaposition of their flamboyant personalities with their decaying, animal-infested environment was exposed in the 1975 cult-classic documentary film Grey Gardens—and has been memorialized many times over in other films, books, and even a 2006 Broadway musical.

Today the interiors of Grey Gardens are a far cry from dereliction—or even the gently worn summer cottage aesthetic one might expect to find inside a century-old shingled seaside home. Instead different essences of femininity filter throughout: A dreamy, romantic spirit pervades the bedrooms; the kitchen, breakfast room, and pool and tennis cabana effuse a bohemian, almost exotic élan; and the wild foyer, sultry dining room, and groovy living room radiate an irresistible gusto not all that dissimilar from the 1960s, ’70s, and ’80s style celebrated to enthralling effect on Lange’s Instagram feed.

It’s a singular mirroring of Lange’s persona and the result of her collaboration with designer Mark D. Sikes, artists and artisans from around the world, and close friend and designer Jonathan Adler, who helped her add a layer of glamour to the living spaces on the first floor. “It’s a lot to live up to, such a famous house, so the decorating had to be bold and original,” says Adler. “Liz has always embodied a true idiosyncratic style with swagger. You can see it in the way she lives and in [her creative direction of] Figue,” which has launched a line of tableware under Lange’s lead.

Of course, idiosyncratic style has permeated the house from the beginning. “A lot of Shingle Style is a reinvention of something else. It’s a vehicle for dabbling in eccentricities,” notes architect James Shearron. “How wonderful that Grey Gardens fell into the hands of someone who has the same kind of spirit as its most famous owner.”

Even with a thoroughly reimagined point of view, the house is not entirely exorcised of the Edies’ presence. Lange tasked a handful of artists with interpreting their spirit: In the foyer, a painting of Little Edie in a headscarf by Helen Downing offers a charismatic greeting, while the second-story landing features papier-mâché busts of Big and Little Edie by artist Mark Gagnon; illustrations of the pair by Jason O’Malley float above a guest room headboard. The works represent “a wink or nod to the former owners,” says Lange—or ghosts, perhaps, of her own making.

Featured in our January/February 2023 issue. Interior Design by Jonathan Adler and Mark D. Sikes; Architecture by Bories & Shearron Architecture and Ferguson & Shamamian; Landscape Design by Deborah Nevins; Photography by Pascal Chevallier; Styling by Hilary Robertson; Produced by Cynthia Frank and Brad Comisar; Florals by The Bridgehampton Florist; Written by Steele Thomas Marcoux